Hindering or enabling alternatives? From short to long transitions

In recent years, so-called “transitions” have proliferated, particularly those focused on climate change mitigation, giving special consideration to the energy sector. An example boosting this perspective is the European Union's Just Transition Mechanism, involving new regulations and funding opportunities, along with new conditions for international trade.

The idea of “transitions” has become quite popular, and although different meanings are involved, the term is being used by politicians, academics, labor unions, and even citizen groups. Sometimes, the term refers to specific goals, like electrification, but in other cases it may be used to describe more holistic and ambitious endeavors, e.g., socio-ecological transitions. These fundamental differences are obscured when the same word, transition, is used.

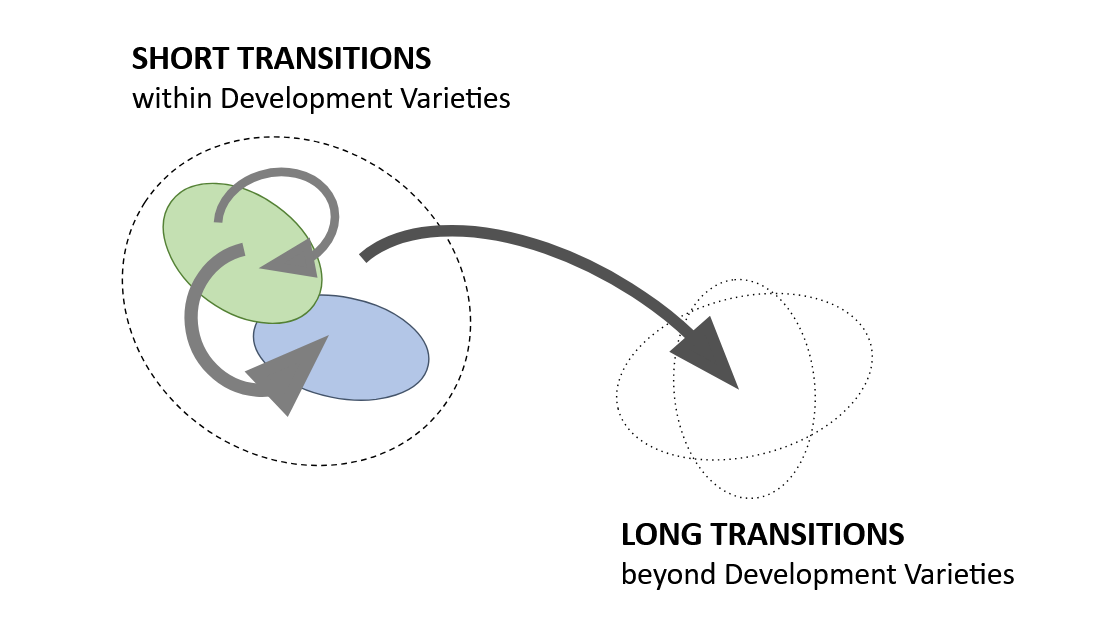

The heterogeneity of perceiving the term transitions must be analyzed; otherwise, critical contradictions and limitations are being overlooked. Some proposals represent a “short” transition to goals that are only reforms of current development strategies, while others aim for “long” transitions to reach more ambitious ends. This distinction has relevant policy implications because many Northern transitions are short and preclude or inhibit long transitions in the South.

The concept of transitions

The word "transition" in English and Spanish means to move from one state to another, which refers to its Latin root of moving. Transitions can be rapid but not sudden; they are distinct from revolutions, for example.

Commonly, this key feature of transitions is not properly addressed. It is an idea that cannot be handled in isolation, because it always refers to two conditions. First, a diagnosis of a current situation, which is usually considered negative, unjust, and intolerable, and which is to be overcome. Second, alternatives are postulated with the purpose of solving the present situation, which is expressed in ideas, sensibilities, and aspirations. Transition refers to the transit, moving from one situation to another. Therefore, the ideas and actions that constitute transitions depend on their starting points and the desired ends. Hence, any postulation of a transition is incomplete without a description of both the present situation and the goals of the alternatives.

Transitions with uncertain goals

Once the strict content of the idea is clear, the problem that recurs today is that many transitions have become ends in themselves. The goals to be achieved are not adequately stated, nor are the current conditions to be overcome properly assessed. This is a serious limitation that goes unnoticed, although it has notable implications.

Clear examples are many proposals for energy and climate change transitions being pursued in industrialized countries. They focus on electromobility or the expansion of electric power as their main aim. Those changes in electric sources become an end in themselves, but the final consumption of electricity, the impacts of its generation and use, and the implications of these changes for other countries are not adequately considered (a recent example is the guide for the G20 by the OECD, 2024). Furthermore, these proposals, although fitted to the conditions of industrialized countries, became global programs that should be followed by other regions (examples are the transitional proposals for Africa, Sokona et al., 2023, or Latin America, Alfonso et al., 2023).

Transitions within development

Depending on their goals, either explicit or implicit, different transitional proposals can be identified (following Gudynas, 2024). One set corresponds to transitions that are reforms or adjustments within a variety of development. These include technological or managerial changes, such as expanding solar or wind energy sources or new regulations on the private sector, but do not address other components of the productive process. Examples of these transitions are the proposed replacement of fossil fuel vehicles with electric ones, but without addressing the role the personal car, its ecological footprint, or its effects on urban settings play.

A second set of transitional proposals refers to measures that represent more ambitious goals, aiming at a transit from one type of development to a different one. These include transitions that reject neoliberal development styles and propose varieties with more intense state intervention. Examples of these positions include several social democracy platforms, Joseph Stiglitz's (2019) progressive capitalism, Mariana Mazzucato's (2022) plans to save capitalism, and the Davos Economic Forum's call for the reset of capitalism. These positions argue that conservative development styles have substantial social and environmental impacts that cannot be resolved through adjustments, so they propose reforms in other areas, such as strengthening the State, although still based on conditions like economic growth.

Since these two types of transitions occur within the current ideas of development, they are identified as short transitions. Their goals are assumed to be framed within Western knowledge of development as progress, fueled by economic growth, that needs the appropriation of natural resources, operating in markets in which capital flows and property is allocated. Even if they are described as a just transition, the plans of the European Union correspond to a short transition, as the European Green Deal frames them with objectives like achieving net-zero emissions while ensuring economic growth. This is not new, because other well-known development adjustments proposed over the last decades repeatedly showed similar limitations. This is the case of the sustainable, endogenous, integral, and human versions of development.

Transitions beyond development

A third set of proposals starts with a different diagnosis, and therefore, their alternatives are more ambitious. They question the conceptual and ideological foundations of development in all its forms, considering these to be the root causes of social and environmental crises. Thus, the proposed alternatives transcend Western notions of development. This results in long transitions.

Applying this perspective, the climate crisis is approached very differently since it requires discussing not only the energy sector, but also other sectors and the ways in which productive processes are organized and operated. This approach requires moving beyond the notion of economic growth (albeit differently from degrowth as understood in Europe). Additionally, it incorporates other spheres, such as politics and culture.

There are several examples of long transitions. One outstanding case is the oil moratorium in the Amazon following the recognition of intrinsic values in the environment. Western knowledge and all development ideas conceive that only humans have value, and hence they are subjects. Nature is a set of objects. This perspective fragments the environment into objects that are useful or have economic value to humans and ignores all other ones. Rights of Nature, on the other hand, is based on the recognition of intrinsic value in the non-human, regardless of its utility in human eyes. In the case of the Amazon, these Rights of Nature impose a mandate to protect the rainforest and its biodiversity regardless of potential economic profits. Therefore, oil exploitation became impossible. Thereby, long alternatives rest on a different theory of value. These and other components are part of the Andean-Amazonian notion of Buen Vivir (see Gudynas, 2011).

The long transitions are reminiscent of the traditional use of the term. Through much of the 20th century, the term "transition" was applied to ambitious and extensive political, social, and economic change. From the 1960s to the 1980s, debates about transitions to socialism proliferated in Western Europe and the Global South. From the early 1990s onward, the term was used in Eastern Europe in the opposite direction: a transition from state socialism to democratic openings and market economies. At the same time, the word was used to describe democratization processes following dictatorships (e.g., in Spain and Portugal, and also in the Global South). In all these cases, the term referred to transformations that affected society as a whole. From this point of view, it would not make sense to refer to specific sectoral change as a transition (e.g., energy transitions), since social and environmental transformations within society are absent.

Implications, influences, distortions, and contradictions

As can be seen, short and long transitions are quite different in that they respond to diverse diagnoses and ambitions for change. Short transitions do not question notions of development — and therefore not those of capitalism — and are often disconnected from outcomes.

From the perspective of the Global North, an example of this short transition is the promotion of lithium battery cars, one of the major targets of the EU Green Deal, without adequately discussing whether it is acceptable to persist in personal vehicles despite their environmental and social impacts. Meanwhile, to the Global South, the conversion of electricity sources, such as the promotion of solar, wind, or hydroelectric sources (qualified as "renewable") to replace fossil fuel sources, is also presented as a transition (see Campanini, 2025 for these and other examples). However, this transition primarily reallocates economic activity to sectors with a significant environmental impact, such as mining. For example, in Chile, large solar panel and wind farm projects are implemented, while mining, the sector that consumes the most electricity (34% of the country’s total), remains untouched. The end consumption of energy should be addressed, but this is not done in short transitions.

Avoiding radical criticism of development, short transitions are accepted by a wide range of stakeholders and are gaining popularity. These transitions can easily overlap with labels such as "sustainable mining", "green", or "ethical lithium", becoming functional to conventional development. At the same time, these formulations render options that challenge fundamental underlying concepts such as ownership, capital, and the market — typical for long transitions — unacceptable or impracticable.

Short transitions are further reinforced through other channels. Although some are specific to industrialized countries, they are not described as, e.g., "European transitions", but rather as global. The Global North has disproportionate power in determining what is or is not global. By framing their transitions as planetary, they also gain legitimacy in the Southern countries and societies.

These “global” transitions are also imposed or promoted through political and trade channels. For instance, the EU's Just Transition Mechanism has intense effects within Europe but also in the international arena, through its trade and investment policies (particularly with countries that have free trade agreements or are in negotiations, like the MERCOSUR). Additionally, beyond postures and intentions, multiple stakeholders in the Global North, such as businessmen, trade unions, universities, foundations, and NGOs, are implementing their versions of the transitions, influencing and reinforcing the concepts in their counterparts in the Global South.

These paths produce different impositions, influences, and limitations in the Global South, affecting both political and civil society and resulting in different consequences.

In some cases, thematic deformations occur. One example is energy transitions in the Global South aimed at reducing CO2 emissions from the energy sector. This is not inherently wrong, but some of them resemble those specific to industrialized countries, in which the energy sector accounts for the largest share of emissions. In most nations in the Global South, however, deforestation, land use changes, and agriculture are the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions, and the main gases emitted are CO2 and methane. Note that in countries such as Colombia and Peru, emissions from rural areas account for more than half of the total greenhouse gases, and in Brazil, they exceed those from the energy sector. Therefore, energy transitions common in industrialized countries that focus on the energy sector alone are inadequate in developing countries. To address climate change in these countries, agricultural and forestry policies would need to be addressed to promote alternatives in land ownership and agricultural production.

Short transitions can block long transitions. Electromobility proposals in industrialized countries require lithium batteries, increasing mining in South American countries such as Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. These mining activities have a range of social and environmental impacts that are being reinforced. Therefore, short and long transitions work in conflicting directions, as long transitions seek to abandon extractivism. The topic has been discussed in the region since the late 2000s, though it is largely ignored in current debates in political and academic circles in the North. This results in the short energy transition in the North, preventing a long transition in the Global South.

There are transitions that run in opposite directions. Long transitions aim to ensure environmental quality and agriculture that provides healthy food. However, short transitions that promote large expansions in electricity generation through extensive solar panel fields result in the loss of agricultural land, making it impossible to achieve the goals of long transitions, as is the case in Chile.

Other alternatives are required

Critical development studies show that the current polycrisis requires alternatives that address several fields, always including social and environmental issues, as they are closely linked. Furthermore, they must reach the root ideas, sensibilities, and practices that are the foundations of development. Traditional Western alternatives in many cases fail, in others result in only temporary improvements, leading to a further deterioration of the social and ecological situation. It is time for options that are beyond the notions of development. That goal implies transitions that must be plural, not universal, and framed within the ecological, historical, and social contexts of each region.

___________________________________________

About the Author

Eduardo Gudynas is a senior researcher at the Latin American Center for Social Ecology (CLAES) and at the Documentation and Information Center Bolivia (CEDIB). He was the first Latin American person to hold the Arne Naess chair on environment and global justice at the University of Oslo. Furthermore, he has been involved with different civil society organizations in Latin America facing environmental and development conflicts over the last three decades.

___________________________________________

References

Alfonso, M. et al. 2023. Hacia una transición justa en América Latina y el Caribe. Resumen de Políticas IDB-PB-00383, BID (Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo), Washington.

Campanini, O. (ed) 2025. El rol de China en la extracción de litio en América Latina. Cochabamba: La Libre.

Gudynas, E. 2024. Transiciones: cortas o largas, reformistas o transformadoras, ajenas o propias. Informe Global, Observatorio de la Globalización, 1: 1-12.

Gudynas, E. 2011. Buen Vivir: today’s tomorrow. Development 54 (4): 441-447.

Mazzucato, M. 2022. Mission economy. A moonshot guide to changing capitalism. London: Penguin.

OECD. 2024. The role of the G20 in promoting green and just transitions. OECD, ILO, UNIDO and United Nations.

Sokona et al. 2023. Just Transition: A Climate, Energy and Development Vision for Africa. Independent Expert Group on Just Transition and Development.

Stiglitz, J.E. 2019. People, power, and profits. Progressive capitalism for an age of discontents. New York: W.W. Norton.

.png)